For decades, Korea’s startup economy has thrived on the tension between imitation and invention. That tension has just become costlier. President Lee Jae-myung’s administration has raised the penalty for corporate technology theft from KRW 2 billion to KRW 5 billion.This means South Korea has drawn a red line between open innovation and industrial predation. But he question is not whether this fine will deter theft—but whether it can change behavior embedded in Korea’s corporate DNA.

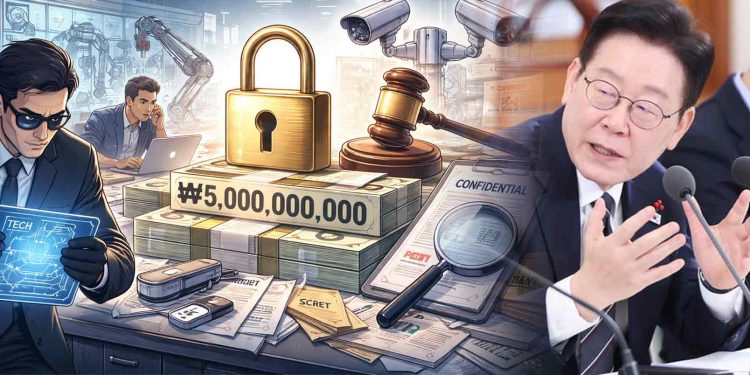

Government Raises Technology Theft Fine to ₩5 Billion Under 2026 Growth Strategy

During the 2026 Economic Growth Strategy briefing, the government confirmed a sweeping plan to address structural unfairness between large corporations and small firms. Among the most consequential measures is the almost-tripling of fines for technology misappropriation, long a source of friction between conglomerates and suppliers.

The “Three-Tier Sanction Package” strengthens administrative and financial penalties. What once ended with a corrective recommendation may now escalate to formal orders, demerit points, and multi-billion-won fines.

The government will also expand the Supply Price Indexation System to cover energy costs, curb late payments in subcontracting chains, and create a Relief Fund for SMEs harmed by unfair trade.

Most importantly, this policy was shaped by President Lee Jae-myung’s own words. At a prior ministry briefing, he remarked,

“If a company earns KRW 100 billion by stealing technology and pays only KRW 2 billion in fines, anyone would steal.”

The comment resonated across Sejong’s bureaucracy. And within weeks, the fine ceiling was raised to KRW 5 billion—an unmistakable signal that leniency had become untenable.

Korea’s Crackdown Signals a Turning Point in Innovation Policy

Technology theft is not new. What’s new is Korea’s recognition that it has long operated as a hidden tax on innovation—collected not in money, but in trust.

For years, small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and startups tolerated imitation as the unspoken price of working with chaebols. The 2024 government survey estimated nearly 300 cases of technology infringement per year, with average damages of KRW 1.8 billion per company. Most victims stayed silent, aware that compensation rarely covered the loss and that pursuing justice risked business retaliation.

By treating technology theft as a corporate misdemeanor rather than an economic crime, Korea allowed its innovation ecosystem to absorb decades of unaccounted losses. The 2026 reforms mark a clear shift: raising the cost of misconduct high enough that imitation ceases to be profitable.

As Professor Lee Byung-heon of Kwangwoon University noted,

“Raising the ceiling to KRW 5 billion will at least make large corporations think twice before misappropriating technologies from smaller firms or startups.”

His observation frames the fine not as punishment, but as deterrence—a way to make exploitation uneconomical.

Professor Oh Dong-yoon of Dong-A University went further:

“Just as severe sentences for murder serve as a societal signal, heavier fines for technology theft send a warning that such acts are intolerable. Cooperative growth alone cannot solve this issue; punitive deterrence is necessary.”

Together, these views capture the deeper intent behind the policy: to redefine innovation not as imitation made efficient, but as ownership made defensible.

Why Enforcement May Struggle Despite Stronger Technology Protection Laws

But changing incentives on paper rarely transforms conduct in practice. The gap between policy ambition and enforcement capacity remains wide.

Korea’s SMEs still face steep hurdles in proving ownership or misuse of proprietary technology. Legal discovery systems are limited, and many firms fear retaliation if they press charges against major partners. The government’s promise of a “Korean-style discovery mechanism”, where a neutral intermediary verifies technology use and contract compliance, is still under development. Until that system matures, deterrence may remain symbolic.

Moreover, the KRW 5 billion fine—while headline-grabbing—applies only after investigation and judgment. Few cases make it that far. Without faster investigative processes and stronger institutional backing, startups may continue absorbing losses quietly, as they always have.

What Korea’s New Technology Theft Law Fixes—and What It Still Can’t Reach

The new framework gives the government sharper tools. Administrative agencies can now issue binding corrective orders rather than suggestions. Victims can include R&D expenses in damage calculations, recognizing the real cost of innovation loss. And by earmarking 20% of the Fair Trade Commission’s collected fines into a relief fund, Seoul is converting penalty revenue into tangible SME protection.

Yet the reform stops short of tackling structural dependencies. Many startups remain financially or technologically entangled with large conglomerates. Deterrence cannot work if survival still depends on the very entities capable of exploitation.

To shift that balance, Korea’s innovation policy will need to combine enforcement with capital diversification—encouraging venture-backed alternatives that reduce overreliance on corporate partnerships.

How Korea’s IP Crackdown Reshapes Trust for Global Investors and Founders

For international founders and investors, Korea’s move is a signal of institutional maturity. It shows a government willing to confront one of its most uncomfortable truths: that economic growth built on subcontracting and imitation cannot sustain a global innovation brand.

The reform also aligns Korea with broader OECD intellectual property standards, reassuring foreign partners who have historically hesitated to share proprietary technologies with Korean firms. For global venture capital, this could restore confidence in Korea’s deep-tech and advanced manufacturing sectors, where IP protection often determines cross-border collaboration.

However, international observers will judge the law not by its text but by its outcomes—by whether Korea can prosecute its own giants with the same rigor applied to smaller offenders. Now this remains untested territory.

Korea’s Next Test: Can Policy Outrun Its Own Innovation Debt?

Finally, the fine increase is not merely punitive, but also philosophical. Korea is acknowledging that every stolen patent, copied process, or coerced design has been an invisible levy on progress. Raising the cost of technology theft is, in effect, raising the value of originality.

But policy can only do so much. For the startup ecosystem, the deeper challenge lies in cultural transition: moving from a risk-averse, hierarchy-driven model to one that rewards ownership, transparency, and fairness. Until that shift takes root, innovation in Korea will remain both an opportunity and an unpaid debt.

🤝 Looking to connect with verified Korean companies building globally?

Explore curated company profiles and request direct introductions through beSUCCESS Connect.

– Stay Ahead in Korea’s Startup Scene –

Get real-time insights, funding updates, and policy shifts shaping Korea’s innovation ecosystem.

➡️ Follow KoreaTechDesk on LinkedIn, X (Twitter), Threads, Bluesky, Telegram, Facebook, and WhatsApp Channel.