The loudest startup stories are still about funding rounds and national AI ambitions. The quieter signal is a workforce that is struggling to enter the system at all. Korea’s latest youth employment data reads less like a temporary dip and more like a structural squeeze: fewer entry paths, more “resting” young people, and a labor market that increasingly rewards experience first. That mix matters for any country trying to build a startup-centered economy.

Youth Employment in Korea Drops for 21 Straight Months

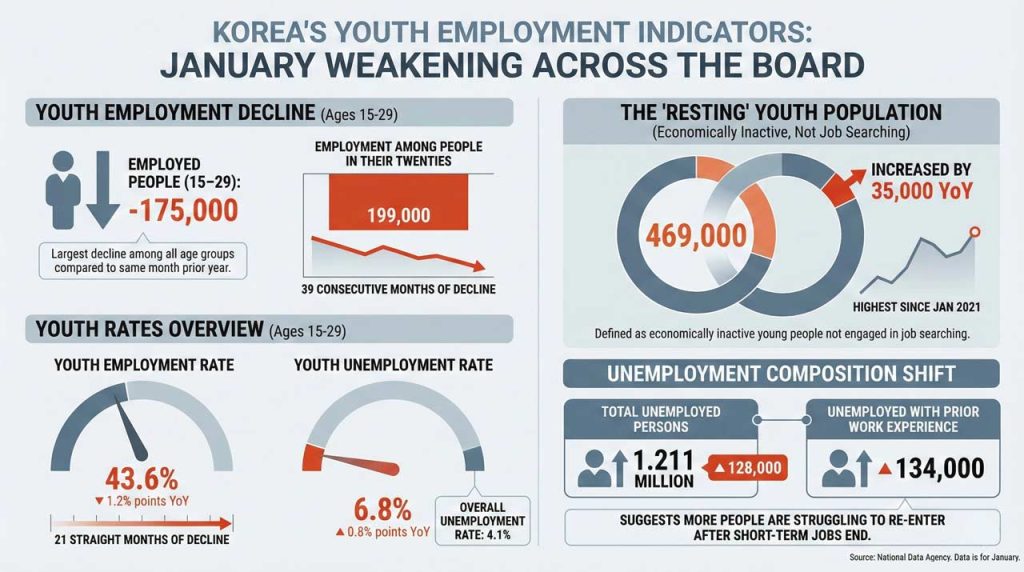

In January, Korea’s youth employment indicators weakened across the board, according to the National Data Agency.

The number of employed people aged 15–29 fell by 175,000 compared with the same month a year earlier, the largest decline among all age groups. Within that, employment among people in their twenties dropped by 199,000, extending a decline that has continued for 39 consecutive months.

The youth employment rate came in at 43.6%, down 1.2 percentage points year-on-year, marking 21 straight months of decline. The youth unemployment rate rose to 6.8%, up 0.8 percentage points, while the overall unemployment rate was 4.1%.

The “resting” youth population, defined as economically inactive young people not engaged in job searching, reached 469,000. It increased by 35,000 year-on-year and was the highest since January 2021.

The composition of unemployment also shifted in an uneasy direction. Total unemployed persons rose to 1.211 million, up 128,000, and the number of unemployed with prior work experience increased by 134,000.

That suggests more people are struggling to re-enter after short-term jobs end.

Why the Talent Entry Route Is Narrowing for Korea’s Startups

This is not only a labor market story. It is a pipeline story.

Startups and scaleups compete for early-career talent, yet Korea’s entry-level channel is narrowing. The data points to fewer young people holding stable jobs, more stepping away from search, and a growing pool of workers cycling through short-term roles.

Government officials point to structural hiring changes. Large-company open recruitment has shrunk, while experience-based rolling hiring has expanded, raising entry barriers for young job seekers.

Bin Hyun-joon, director general of social statistics at the National Data Agency, said,

“While it is not confirmed by official statistics, it is presumed that even entry-level hiring in professional occupations such as lawyers and accountants has decreased under the influence of the spread of artificial intelligence (AI).”

The Bank of Korea has also flagged technology-driven shifts in youth job demand. In a recent report, it classified professional services, information services, publishing, and computer programming and systems integration and management as industries with high AI exposure and said youth employment declines have been observed in those sectors after the launch of ChatGPT.

For Korea’s startup ecosystem, the key point is not that AI is “taking jobs” in a simple sense. It is that entry roles are becoming harder to access in precisely the sectors that feed talent into startups.

AI Investment Rises While Entry-Level Opportunities Shrink

Korea’s policy narrative emphasizes innovation, deep tech, and AI competitiveness. Yet the labor market reality looks different at the bottom of the ladder.

AI-heavy sectors often reward specialization and experience. Entry-level positions in professional and information work can be the first to be reshaped when automation reduces routine tasks. That can leave young workers with fewer “training ground” jobs where they build experience.

The tension shows up in the statistics. Youth employment has been declining for nearly two years, and the “resting” category has reached its highest level since 2021. That is not a sign of a talent shortage. It is a sign of a talent bottleneck.

This also reframes the meaning of “startup-centered society.” A startup economy does not only require capital and technology. It requires early-career pathways that turn graduates into productive operators. When those pathways narrow, startups face a thinner layer of hire-ready talent, even if the country is investing aggressively in AI.

What the Youth Employment Data Shows — and What It Cannot Yet Prove

The verified data supports a clear conclusion: youth employment conditions have deteriorated, entry barriers are rising, and more young people are outside the labor market.

It does not prove that AI alone is the primary cause. The reports also cite weak domestic demand and structural hiring shifts that favor experience.

It does, however, show why “AI impact on entry level jobs” is becoming a policy-sensitive question. When youth employment declines appear in AI-exposed sectors, and officials openly point to AI as a factor in reduced entry hiring, the transition problem becomes harder to ignore.

One practical sign is the rise of short-term work dependence.

A survey by Alba Heaven of 1,331 part-time workers reported the fact that 66.9% planned to work during the Lunar New Year holiday. Over 70% in food service, beverages, driving, delivery, distribution, and sales said they intended to work during the break. Among those working, 32.8% planned to take additional short-term jobs alongside their existing work, with pay as the top selection factor.

This is coping behavior, not career formation.

What Global Founders and Investors Should Understand About Korea’s Hiring Shift

Therefore, the message for global founders considering Korea is not that talent has disappeared. It is that the path into stable work is getting tighter, and young workers are increasingly pushed into short-term income survival. That can affect hiring dynamics, wage expectations, and retention.

As for international investors, youth employment weakness is a leading indicator worth watching. Startup ecosystems thrive when early talent can enter, learn quickly, and scale with companies. A growing “resting” cohort and rising youth unemployment can become a drag on long-term workforce quality if the gap persists.

Meanwhile, this also results in operational implication for cross-border partners. Korea’s push into AI and deep tech may produce global champions, but the supporting talent pipeline needs deliberate work.

So training programs and transition support, such as MSS-MOEL’s AI-based training program, become more than social policy. They become ecosystem infrastructure.

A Startup Economy Needs Entry Doors, Not Only Advanced Labs

Finally, Korea is trying to win a future built on AI, deep tech, and startups. That goal is rational. The risk lies in assuming the workforce will smoothly follow.

A startup economy is only as strong as its entry points. When the first rung of the ladder breaks, the country does not only lose jobs. It loses momentum, confidence, and the next generation of operators who turn policy ambition into companies that actually scale.

Key Takeaways for the Korea Startup Talent Outlook

- Youth employment in Korea fell by 175,000 year-on-year in January, the largest decline among all age groups.

- The youth employment rate dropped to 43.6%, extending a decline that has lasted 21 consecutive months.

- The youth unemployment rate rose to 6.8%, while the overall unemployment rate was 4.1%.

- “Resting” youth reached 469,000, the highest level since January 2021.

- Government officials cite reduced open recruitment and experience-based hiring as rising entry barriers.

- A National Data Agency official said entry hiring in professional jobs may have been affected by AI, though not confirmed by official statistics.

- The Bank of Korea has flagged youth employment declines in AI-exposed sectors after ChatGPT’s launch.

- Growing reliance on short-term work signals a widening gap between income survival and career entry.

🤝 Looking to connect with verified Korean companies building globally?

Explore curated company profiles and request direct introductions through beSUCCESS Connect.

– Stay Ahead in Korea’s Startup Scene –

Get real-time insights, funding updates, and policy shifts shaping Korea’s innovation ecosystem.

➡️ Follow KoreaTechDesk on LinkedIn, X (Twitter), Threads, Bluesky, Telegram, Facebook, and WhatsApp Channel.