Korea is trying something unusual for a high-income economy with a mature bureaucracy, it wants a mass-participation startup audition to fix a structural problem that policy has struggled to touch. “Startup for All” is not framed as a grant program or a campus-style accelerator. It is being sold as a national culture shift, with cameras, brackets, and a public finale. The bet is that visibility can move behavior faster than incentives alone.

“Startup for All” Project: A National Startup Audition

On January 30, the Ministry of SMEs and Startups (MSS) and the Ministry of Economy and Finance (MOEF) unveiled “Startup for All” project (also known as “Everyone’s Startup” Project”) at the Blue House during the National Startup Era strategy meeting, “K-Startups Build the Future,” according to reports by Newsis, Yonhap, Seoul Economic Daily, and Money Today.

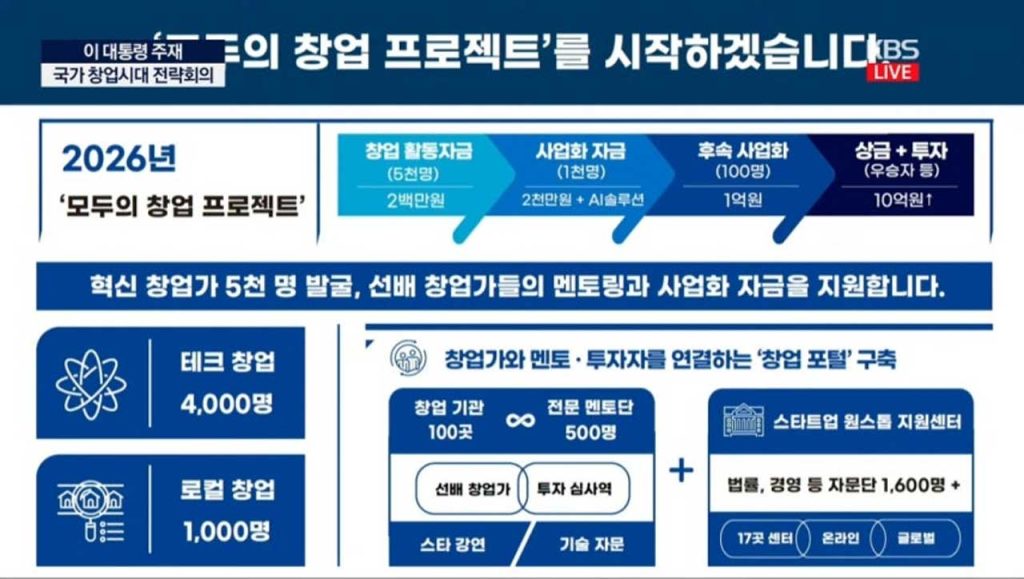

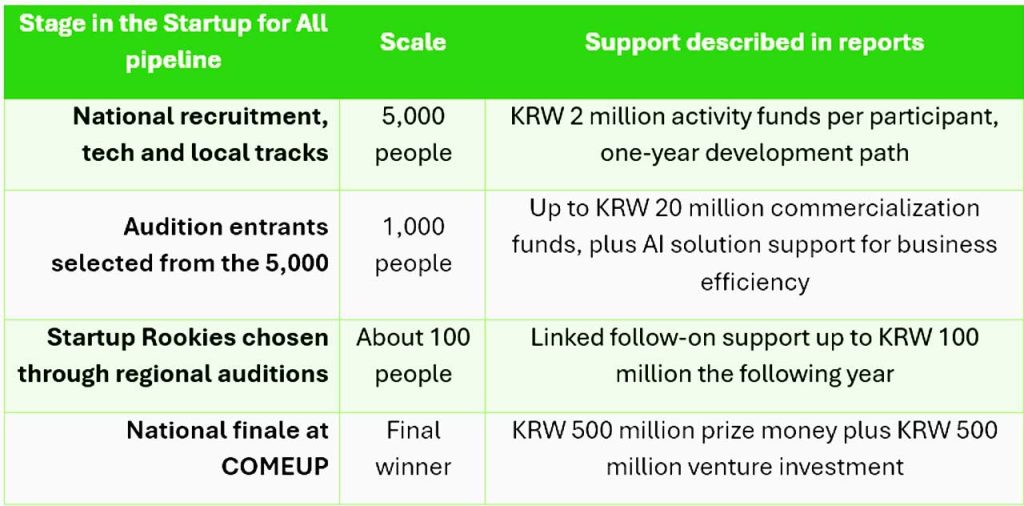

The program is designed to recruit 5,000 aspiring founders nationwide, split into 4,000 tech-track participants and 1,000 local-track participants.

All 5,000 receive KRW 2 million in startup activity funds for a one-year founder development path. A mentor network is attached, including 500 senior founders and roughly 1,600 experts who will serve as “Startup for All supporters,” as described across Newsis and Yonhap coverage.

The competitive pipeline then narrows. About 1,000 participants enter staged auditions, starting with preliminaries across 17 cities and provinces, then advancing through five regional finals. The government expects to select around 100 “Startup Rookies,” who later compete at COMEUP, Korea’s flagship global startup festival, where the final winner is chosen. Multiple outlets report the grand prize package as KRW 500 million in cash plus KRW 500 million in venture investment.

Minister Han Seong-sook framed the policy shift as a move away from screening support projects and toward investing in people, adding that the goal is to create an environment where anyone can try and where failure becomes an asset.

President Lee Jae-myung, after hearing the plan, suggested the once-a-year cadence is too small and raised the option of using a supplementary budget to run additional cohorts.

Why Korea is Tying Entrepreneurship to “K-Shaped Growth”

The government’s explicit diagnosis is political and economic at the same time. Several reports cite that growth outcomes have been concentrating among large firms, the capital region, and experienced workers, while SMEs, regional communities, and younger cohorts see less spillover, described as “K-Shaped Growth.” “Startup for All” is positioned as a corrective, not simply a startup promotion campaign.

That matters for the ecosystem because it expands what “startup policy” is supposed to do. The project is meant to seed founders at scale, then keep them in the system through the next structured steps: tech commercialization support, local commercial district building, and a formalized re-challenge pathway.

The same policy package also includes plans such as building 10 startup cities by 2030, creating 50 local hub commercial districts and 17 “glocal” districts, and pushing sector programs for deep tech areas like defense, climate tech, and pharmaceutical bio.

It is also designed as a visibility engine. The government plans to produce the process as a startup competition program, with the stated intention of spreading entrepreneurship culture.

The Friction Point: Auditions Reward Storytelling Faster than Companies Mature

A national audition format solves one problem and creates another. It lowers the psychological barrier to entry, simplifies application requirements, and makes entrepreneurship socially legible.

At the same time, it risks turning founder selection into performance under the spotlight. The state is effectively saying that public attention is now a policy tool.

Not to mention the heavy execution burden. This project connects 5,000 participants, 100-plus startup institutions, 500 senior founders, 1,600 experts, and multiple rounds of regional auditions. Programs at this scale often fail quietly through inconsistent mentoring quality and uneven local implementation.

The government knows there’s a risk of fake applications or corruption in such a large-scale audition program. Yonhap said officials mentioned that they’re setting up specific response plans to deal with false plans or illegal broker involvement.

There is also a timeline mismatch. Startups rarely become investable on an entertainment schedule. Yet the national finale sits inside COMEUP, and the top-line outcome is an “over KRW 1 billion” prize-plus-investment package for the final winner. That creates pressure to pick teams that look ready on stage, even when the deeper work is customer validation and iteration.

What “Startup for All” enables, and What It Still Does Not

“Startup for All” project enables three things immediately.

First, it creates a broad funnel. KRW 2 million per participant is small capital, but it buys permission to start, especially for first-timers outside Seoul.

Second, it builds a defined ladder with concrete milestones and numbers that are easy for the public to understand. Below is the clearest way to map the pipeline based strictly on the figures in the reports.

Third, it formalizes re-challenge credentials. The government plans to issue a “challenge resume” that records participation and a “failure resume” that can be used later when applying to government startup programs, along with a re-challenge platform and a youth-focused challenge school.

What it still does not solve is the hard middle, sustained company-building capacity. A one-year funnel can create momentum, but it does not automatically fix market access, procurement bottlenecks, or private capital’s risk appetite. Even the “Startup Boom Fund,” reported as KRW 50 billion in multiple sources, is designed to concentrate investment into rookies, not to provide broad survival capital to the full 5,000.

Why “Startup for All” Project Matters for Global Founders and Investors

For global founders watching Korea, “Startup for All” signals an institutional pivot. Korea is trying to manufacture founder supply and social legitimacy at the same time. That is unusual for an OECD economy with strong incumbents and a risk-averse labor market.

For international investors, the implication is not the KRW 2 million seed money. The signal is the state’s willingness to build a nationwide pipeline, then attach procurement, public data access, and corporate and public-institution proof-of-concept opportunities for the tech track. If those linkages work, they can reduce early go-to-market friction for teams that would otherwise remain local.

For cross-border partners, the local track is the sleeper element. The policy explicitly ties local entrepreneurship to commercial district building and tourism-linked “glocal” zones by 2030. That creates potential entry points for retail, mobility, travel tech, and regional commerce platforms that want pilots outside Seoul.

Funding Startups and Rewriting What “Failure” Means

The most consequential line in this policy package is not the prize pool. It is the attempt to turn failure into an administratively recognized credential. Korea has long supported re-challenge programs, but “failure resumes” make the intent explicit and portable inside the state system.

If the government follows through, Korea may end up with a clearer, more legible founder track record system than many peer countries. If it does not, the audition becomes a one-season spectacle and founders learn the wrong lesson, that visibility is the product.

The next signal to watch is not the finale, it is what happens to the 4,900 people who do not become “rookies.”

Key Takeaway on Korea’s “Startup for All” Project

- What launched: “Startup for All,” a national entrepreneurship audition announced January 30 by MSS and the Ministry of Economy and Finance at the Blue House strategy meeting, reported by Newsis, News1, Yonhap, Seoul Economic Daily, and Money Today.

- Scale and funding: 5,000 participants, KRW 2 million each in activity funds for a one-year founder path, split into 4,000 tech and 1,000 local.

- Selection pipeline: 1,000 enter staged auditions across 17 provincial preliminaries and five regional finals, narrowing to about 100 “Startup Rookies,” with a national finale at COMEUP.

- Top award: Final winner receives KRW 500 million in prize money plus KRW 500 million in venture investment, as reported across multiple outlets.

- Ecosystem tools attached: Mentoring network of 500 senior founders and roughly 1,600 experts, plus AI solution support and staged commercialization funding.

- Capital follow-through: A KRW 50 billion “Startup Boom Fund” is planned to invest in rookies; a KRW 1 trillion re-challenge fund is also cited in reporting.

- Core tension: A public audition can widen participation fast, but it also risks rewarding pitch performance faster than real companies mature, so execution quality and post-program pathways will decide whether the policy changes outcomes or only headlines.

– Stay Ahead in Korea’s Startup Scene –

Get real-time insights, funding updates, and policy shifts shaping Korea’s innovation ecosystem.

➡️ Follow KoreaTechDesk on LinkedIn, X (Twitter), Threads, Bluesky, Telegram, Facebook, and WhatsApp Channel.